When we arrive at the deserted Kwong Ming Shipyard after a short walk along Tam Kung Temple Road in Shau Kei Wan, Mr Au (亞神) is asleep. His dog eyes us suspiciously and barks the drowsy shipwright awake. Mr Au’s somnolence makes sense for a semi-retired 87-year-old and given the steep decline in the construction of wooden boats in Hong Kong. Boatbuilding has been his livelihood for over 60 years. Things were different in the past, and as recently as the 1990s, his yard produced most of the wooden boats built locally.

The decline of traditional shipbuilding

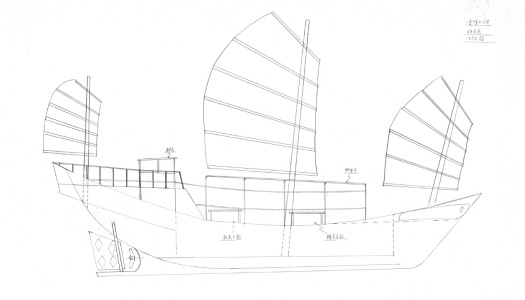

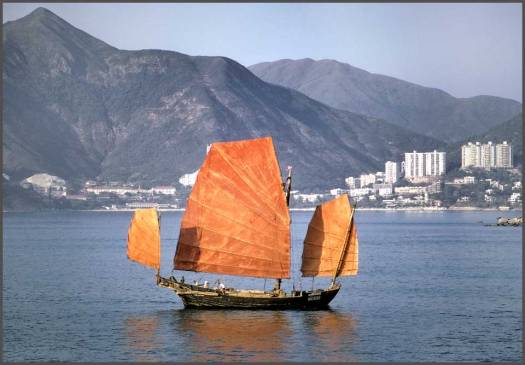

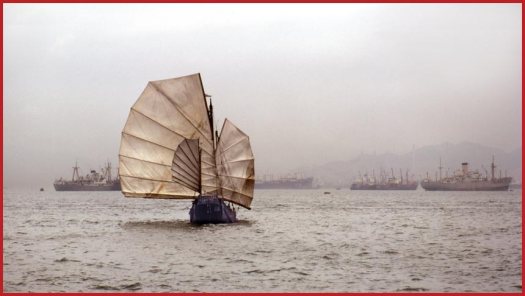

On the face of it, the loss of wooden boatbuilding is a natural consequence of advances in technology, the durability of materials like steel and fibreglass, along with logistical improvements brought by containerisation and a quickly vanishing fishing industry. The vernacular vessel we most associate with the coastal passageways of Guangdong—the Chinese junk under strained, expansive sail—is now obsolete, their old, battered carcasses recycled on the Chinese mainland as firewood or furniture. Very little remains of that bygone age of sail power. The exact date of their demise is hard to determine. Certainly, up to the 1980s and early 1990s, the occasional relic was seen crisscrossing the harbour.

Mr Au says junks no longer function beyond their objectification as “eye-candy” or museum pieces to please tourists. He has built them for over 60 years, having worked at the family shipyard in Shau Kei Wan since first arriving from Macau in the 1950s.

“They’re just to look at. Junks are just to look at,” Mr Au repeats several times during our conversation, “I built a junk for a celebrity and he just put it in the water to look at.”

Junks as eye candy

Indeed, the aesthetic pull of the junk can’t be ignored. The orientalist imagery associated with the traditional Chinese junk remains affecting, something that the Hong Kong Tourism Board (HKTB) is keen to exploit. The city’s signature image remains the bright red silhouette of a junk; inauthentic though they might be, James Clavell fantasies still sell the cinematic romance of the city and its harbour. Few can resist the evocative architecture of the heavily battened red lug sails and the sheen of the lacquered decking. Caught in the right light, the tourist boats dotting the harbour stir the imagination and connect it to an idealised maritime mythology.

Of the current fleet, the only ship originally built as an authentic junk is the delightfully proportioned Duk Ling, a renovated 19th-century fishing vessel and the source for the HKTB’s standard representation of a junk. The vessel was renovated in the 1980s and was more recently refurbished after sinking in the Aberdeen Typhoon Shelter in 2014.

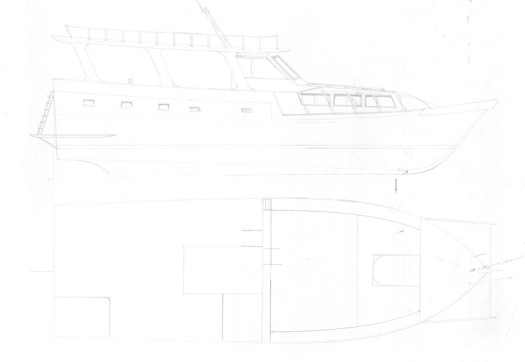

More recently, Mr Au and his son Pao (亞豹) built the Euro-sounding Aqua Luna (Cheung Po Tsai is its Chinese name) for the Aqua Restaurant Group. Father and son were never happy with Aqua Luna’s design, submitted by a naval architect with little experience in traditional Chinese junks. Even to the untrained eye, the exaggerated proportions of the raised stern and the way the Aqua Luna sits in the water makes it obvious that something is awry.

“We told them there was a problem with the design,” explains Pao. “The stern is too high and the proportions are wrong so it raises the bow out of the water. You can see the red antifouling paint above the waterline. It’s embarrassing. They can’t even raise the sail beyond the third batten because the Marine Department has tightened regulations since the Lamma ferry tragedy [in 2012]. Because the passenger seating area is so tall, it makes the sails sit too high up on the mast and it’s too dangerous to raise them as the whole boat could capsize in a strong wind. When we first put it in the water we thought it would sink! We had to weigh down the front but it’s still wrong.”

More celebrated junks built in the Chinese tradition of naval architecture include the legendary ships of Zheng He and the Keying, which famously set off from Hong Kong in 1846 and sailed all the way to England and New York. The Keying’s arrival in the west caused quite the stir: a special medal was minted and the junk’s appearance in New York was noted by P.T. Barnum who had a copy of the vessel built in Hoboken.

Mr Au’s prolific portfolio

There was a time when shipbuilding and craftsmanship mattered. Mr Au has lost count of the number of wooden craft constructed in the yard, but he claims to have had a prodigious output. He estimates that his yard produced up to 80 percent of the wooden boats built in Hong Kong in the 1990s. His handiwork includes numerous sampans and dragon boats, as well as pleasure junks for HSBC and Swire, launches for the Marine Department, and ferries for the Jumbo Floating Restaurant and the Society for the Aid and Rehabilitation of Drug Abusers on Shek Kwu Chau (石鼓洲).

“I built boats 20 percent faster than anyone else,” he notes with singular pride, adding that he could fulfil contracts and commissions that his rivals would turn away out of fear that the jobs might be too challenging.

“I’m a person with lots of guts,” he says, noting in particular his willingness to take on jobs like the construction of three wooden boats for the Hong Kong History Museum. “Nobody would take the job because the museum had already been built and there were a lot of restrictions on building inside, so we built the boats in sections and brought them into the museum to assemble.”

The fact that history museums are some of the few commissioning boats proclaims shipbuilding’s fall from grace in contemporary Hong Kong.

Mr Au’s guts and tenacity have helped his business stay afloat and made certain that old skills stay alive. Although his business—now in the hands of his son—is seeing lean times, the shipyard is buoyed by the prospect of building a second Aqua Luna, which presents a chance to put right some of the mistakes made the first time around. This second iteration, however, will not be built in Hong Kong; it will be built in Kwong Ming’s second yard on the mainland.

The Macanese connection

Macau is Mr Au’s birthplace and it too has seen its historical place as a centre of shipbuilding diminish, perhaps even more dramatically. The deserted shipyards of Coloane linger in the memory, their beams and truss work have begun to splay like the weakening limbs of a ghostly herd of giraffes. Under rusting, corrugated roofs they appear to be sinking, slowly and awkwardly, into the brown silt of the coastal bank. At the height of the shipbuilding industry 1,000 men were employed here but in April the Tribuna de Macau declared that the ‘antigos estaleiros de lai chi vun em risco de colapso.’ Their collapse is indeed imminent; this much is obvious and it is a pessimistic sight.

The day is hot as we trudge along Rua dos Navegantes towards the sharp incline that leads to Lai Chi Vun where there are signs of life. We happen upon Mr Tam who is cheerfully addressing friends and is happy to show us the models of wooden boats he has built in the past: junks, shrimp boats with expansive rigging, robust fishing trawlers. Behind him, pasted diffidently against his office door, is a notice advertising an impressively named exhibition: An Art of Precision: Shipbuilding in Macao: People, Craft and Society, The Estaleiro of Lai Chi Vun. The exhibition took place in 2013. Tam says that the last ship he built was in 2005, which was coincidentally the last ship built at Lai Chi Vun.

Tam’s son, Tam Chon-ip, lectures on traditional ship construction and heritage using knowledge gleaned from an upbringing amongst the timbers and hulls of Lai Chi Vun. He has previously offered tours of the shipyards, in collaboration with Macau’s Cultural Affairs Bureau, delighting visitors with stories of his family’s illustrious past.

Down the hill is the busy Hon Kee Coffee, a cafe owned by Leong Kam-Hon. A former shipwright, Leong transformed a shack amidst the shipyards into a small restaurant selling noodles and coffee. It is Buddha’s birthday and the holidaymakers are out in force. A portrait of Chairman Mao hangs behind a statue of ‘the Great Helmsman’ in the enclosed dining room. Two things strike the visitor: it is a young crowd, drawn by Leong’s delicious, signature frappé, and they are decidedly trendy. Two expensively clad Chinese women arrive by SUV and totter in on heels, happy to wait patiently while the wooden tables are cleared and cleaned. Many years ago Leong was cut badly with a mechanical saw and decided to change careers. Vivid scars trace the entire length of his left arm. He wields a skillet in one hand and a deep fryer in the other, as he regales us with tales of Lai Chi Vun’s former glory. The cafe is doing well and he describes his accident as a blessing in disguise.

“Skills are lost as yards close and shipwrights migrate to China to work or change careers to make ends meet. In the old days boys became apprentices to shipwrights when they had just hit their teens, learning to bend wood, but not anymore”, says Leong. It is a sad denouement to a once proud industry, seeing the signature lug sails of the traditional wooden junk furled for good, their shipwrights downing tools and leaving once clamorous yards to fall silent. Can this really be the end? Will the junk leave our waters, as with Keying and Zheng He’s fleet, into the mists of legend and lore?

In search of the ‘real’ Chinese junk

Some Macanese shipwrights believe that the quintessential Southern Chinese junk was invented in the former Portuguese colony. We make our way to the University of Hong Kong to investigate. Elliott House sits high above the main campus, steeped in low lying mist. Dr. Stephen Davies receives us in his office. The maritime historian needs no encouragement as he launches directly into the meat of the subject. “As of the 16th Century in Macau and as of the 1840s in Hong Kong, there was increasing hybridization in junk construction and structure, which adapted the traditional Chinese manner of building vessels to kind of a halfway house with the western system.” Dr. Davies opened the Hong Kong Maritime Museum in 2005 and ran it for many years. Born into a military family he joined the Royal Navy, training and serving as an officer and Royal Marine. Eventually going on to teach Political Theory at HKU he grew tired of life on land and set sail for 15 years covering 50,000 miles and 27 countries in a 38ft sloop with his partner, Elaine.

On the subject of Chinese seacraft, the eminent mariner becomes animated. According to Davies it is hard to pinpoint exactly what an archetypal junk might be as there have been so many variants. It seems the term is loosely applied to all sorts of Chinese vessels. “What we call a junk is almost certainly a misnomer. Calling every Chinese vessel a junk is like calling every western vessel a dhow. There’s probably as much regional variety in Chinese vessel design as there is in European.” The term ‘junk’ itself originates as a proto-Javanese term that means ‘large vessel, from anywhere, that goes to sea’.

According to Davies, “virtually all Hong Kong designs are actually lorchas”, Chinese junk rigs on European style hulls. Junks (or lorchas) are a direct reflection of Hong Kong’s ethos of pragmatic adaptation. “Hong Kong builders were into hybridization because, on the side, they were building western vessels too. They were all smart cookies and they could see that there were advantages to building in the western style.” Even with this knowledge it is surprising to learn of the Hong Kong junk’s true lineage. “It is in fact an Italian design, adapted by emigrants to California and then adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organization in the 1950s as a design to peddle to the third world to upgrade the productivity of their fisheries.” Local fishermen were initially resistant to the change because “[the] community [believed] that all sensibly built ships had sterns higher than the bow otherwise the god in the shrine at the back of the boat [wouldn’t] be able to see where he or she was going.” To convince the Shau Kei Wan shipbuilders to construct these boats, the newly christened Agriculture and Fisheries Department, underwrote the cost with the understanding that the buyers would pay them back if their yields did increase. It only took one fisherman, who ordered two of these Italo-Californian boats, to return with a bumper catch to convince the community. “When it came down to big income the gods had to adapt.”

Given Southern China’s history it seems natural that junks have taken many different cultural influences. As to what original unadulterated Chinese vessels looked like, historical sources are unhelpful – many accounts of Chinese seafaring, including those of Zheng He’s, are mythologized to the point where it is difficult to separate fact from fable. Few if any old ships exist because of a timber shortage that China has been experiencing since the Ming Dynasty. Says Davies, “China has always used wood as a fuel [and] it’s also used wood as its main building material [and this has] put huge pressure on Chinese timber resources – as ships became old they tended to be recycled.” To add to this, archeological records are poor, leaving very few clear examples of Chinese wrecks to look at. “China has been a very poor country [and] hasn’t been able to afford quality marine archeology up until of late which means that even though they’re sure there are 30-40 wrecks on the Chinese coast they’ve identified only about 15 and done serious excavation on 10.”

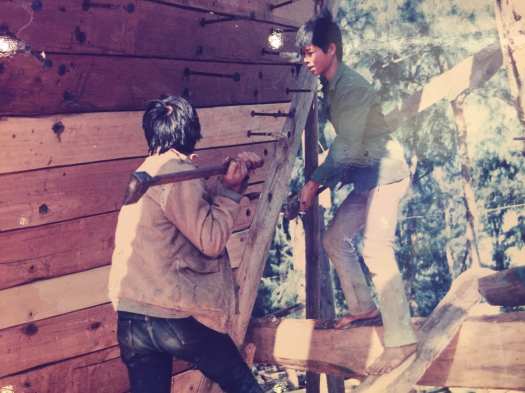

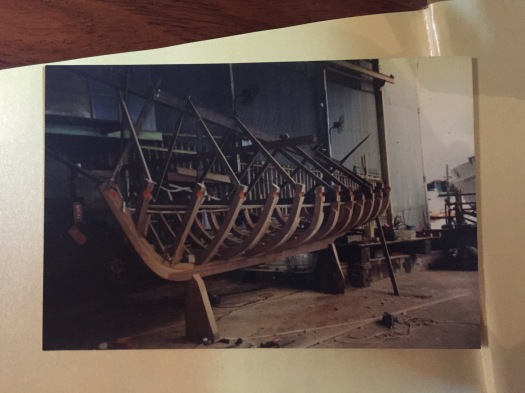

How to build a junk

Despite our disconnect from the past, the old ways still exist. Junks have always been built from hard woods. In the past they came from Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar but these days Kwong Ming either uses teak or an African wood which they call ‘kwun deen’. According to Pao, “you could submerge this wood in water for 50 or 60 years and it wouldn’t change.” Traditionally, wood has been treated by ‘pickling’ in salt water- one old pickling pond is still visible from the Airport Express. According to Davies it is the vernacular understanding that leaving timber in salt water increases its resistance to pests. Pao gives a cursory explanation of the process of construction which starts with the internal structure, around which timbers are bent. The hull is completed by caulking it with a mixture of bamboo fibres and tar. Pao hauls out a large wooden crate from which he produces specialist tools – they’re much bigger than regular woodworking tools and are reinforced with steel, “when you strike them together they make a beautiful sonorous ring”. It takes 9 skilled workers 10 months to complete one large vessel such as Aqua Luna. Workers are highly specialised with shipwrights, such as the Aus in charge of structures and bending timbers, and sailmakers in charge of the rigging. Says Pao, “In the old days you had to work for 3 years before you could call yourself a sifu” but he believes that with dedication, the skills could be learned in a year and a half. Finding students to take up the trade is another matter.

There are now around 20 people in Hong Kong who possess the skill to build a traditional wooden boat, according to Pao. Of those only 3 know how to caulk hulls, of those 3 the youngest is 60 years old. Pao, who is in his 40s is the youngest shipwright in the SAR. “In 8 or 10 years there will be no more” he laments. “Young people wouldn’t do a hard job like this. When it rains you get wet and when it’s hot you work under the blazing sun. As an apprentice you have to get in the water and get boats out of the water. Most would rather work in a cha chaan teng (茶餐廳) at least there they can enjoy the air-conditioning.”

Dr. Davies echos this sentiment – there is no glory or pride in becoming a shipwright in Chinese society. “In the West, historically, the sea [has been] respectable at all levels of society. Aristocrats went to sea, you could make big money as a merchant and become respectable by going to sea. You could gain glory as an admiral, become a great scientist, push your career as a poet, a playwright, a painter or a novelist by having the sea as your subject.” Not so in Chinese culture.

“I keep trying my Chinese art historians and they have never found me a classical Chinese ink painting with the sea as its subject. Not one in the entire canon of Chinese ink painting art from the earliest recorded till about the 1870 / 1880s. I found two Tang dynasty poems that mention the sea but no poem that is about the sea. There is not one person in Chinese history who is a renowned ‘sea person’. Zheng He’s title is not ‘Admiral’, it’s ‘Senior Envoy’. We don’t know the name of a single one of Zheng He’s maritime captains. We know the names of his generals, his clerks, his scientists, his buddy diplomats, but we don’t know a single seaman because China never had that sensibility.” So while European and American shipbuilding traditions thrive the Chinese tradition founders. “It’s using your hands to build something beautiful [and] all of this is the outcome of a revolution because decent middle class chaps who liked the sea and wanted to go play bought old fishing boats and then gradually adapted them so they’d have nice cabins and comfy bunks.” Could pleasure and sport be the saving grace of a dying tradition here in Hong Kong?

Rebirth of an old tradition

As it happens, this is no new notion. The Chinese rig has long had its admirers. In the 60s a Lieutenant Colonel Herbert George ‘Blondie’ Hasler, father of single-handed sailing, pioneered the use of a Chinese-style junk rig on his western yacht, Jester. This allowed him to handle the entire rig from the safety of a central control hatch – Hasler claimed he could make an Atlantic crossing in Jester without leaving his cabin. A wealthy Chinese middle class might have developed an interest in modifying local craft for sport and leisure, and indeed we may have seen the beginnings of that in the 70s and 80s. Had it not been for the ready availability and ostentatious allure of Western style yachts, that trend might have continued and evolved. Now the state of Chinese seacraft design is in stasis.

The potential of Chinese vernacular design is plain to see, and its power and speed can be witnessed today in the most unlikely of places. Says Davies, “we see [the] natural development [of junk rigging] winding in and out of Stanley every weekend – the battened windsurfer sail. That’s where it could have gone if anybody had been interested in [the Chinese rig], aerodynamically.” Some design and imagination could birth a new breed of yacht derived from the Chinese vernacular. At this suggestion the academic sits up in his chair. “Imagine if Pierre de Coubertin (father of the modern Olympic Games) had been taken by the Chinese yu lou (a fishing dinghy propelled by a large single oar) and set up an Olympic competition alongside western rowing- what would the Chinese equivalent of a single skull look like today? How would that have adapted? It would have been carbon fiber, obviously, and some serious sport kit development thinking would have gone into the hull form. There’d be more whip and more power in a yu lou – it’s a hell of an efficient piece of kit, you would be absolutely flying! Imagine if he’d also fallen in love with a small sailing junk and thought ‘hmmm…in the sailing section we’re going to have competitive junks’. What would that be like? What would a racing sampan look like? It would have something rather like a windsurfing sail…it would have hydrofoils like a moth!”

So we leave you here, imagining what could be – the sleek racing junk, shaking off the constraints of nostalgic Chinoiserie and smashing through the confines of museum walls, rising gracefully from the waves on a hydrofoil hull, leaving behind a jet-like wake. Casting aside the heavy teak of its forbears, its glossy black carbon fiber glinting in the morning light. Its crew, a finely tuned unit winching and trimming battened sails, spread like dragon’s wings or geometrically curled into helixes amidst the wash and spray, propelling them at breakneck speed, on winds of change, into the future.

UPDATE:

29 April 2017 – Since the time of original publication the Aus have launched the Aqua Restaurant Group’s second junk. The Aqualuna/張保仔’s sister vessel has been christened ‘Dai Cheung Po’ or 大張保. The junk, which will be known as Aqualuna II in English, was built at Kwong Ming’s Shenwan yard, about an hour away from Zhuhai by car.

Lovely post and very interesting on this special craft. Would love to get to know more about junk building traditions, and hands on! Is there any hope of reviving the boatbuiling traditions in East Asia? Found your blog when searching for books on how to build a Chinese junk. Seemes like no such thing is around.

Hi Marie,

I would also love to build a Chinese craft. I imagine there would be a slight glimmer of hope if the funding was there to incentivise some of these junk builders – they also take some convincing as they’re quite reticent and, in some ways, quite secretive. The most interesting thing to me would be to create an updated Chinese junk rather than a museum piece, as though the design had been left to evolve naturally. What do you think?

Oh, thank you for the reply! I am bummed to have only seen it now.. In the meantime I have encountered a friend with Chinese roots who is very interested in making a documentary about the craft. I can understad the boatbuilders to be scarse about their craft. One must hope they will understand the way of sharing in order to keep the craft alive. I guess they would be more open to do so if someone is actually there learning the trade. I also think to keep boatbuilding alive you have to indeed keep building boats that will be sailing and in use in this day and age rather than a museum piece for show. It would be natural that a boat design would evolve, still always keeping what works best for the purpose and waters of the boat. Do you think there would be any way of establishing an connection between the shipwrights of Hong Kong and for example Hardanger Fartøyverncenter in Norway? Norway is one fine country for keeping these trades alive, and it would be interesting both because of knowledge exchange but also funding.

Well said Marie!

Yes it could be that their are better places for such an appreciation, as this craft to continue!

Also please note, I quit my last post too soon, unable to edit.

I really want to thank all for sharing such lovely work of others, your pages are filled w/interesting stories, as well; http://www.global-mariner.com

if any yet to see!

What a joy to visit where people are living in these boats as they always did, utilizing the function of them! It is this way, that attracts me to visit.

I look forward to reading all of this, thank you all!

kara

Hello Dan,

I can understand your desire, for we too once had it.

We once picked up some sheets from a Museum, of a Chesapeake Bay Schooner, that was designed for one personally, a smaller version, as he died before building it. I think w/ very long bow sprit it was 69 ft? The designer’s wife had just taken them to the Museum on the E coast. The person working the Museum in that department w/boat sheets, was very informative and kind. It was a planked wood design and then we took it to Reul Parker, a builder/designer that converted it to cold molding. He did a nice job, but then we were unable to build it, so we still have the plans and would sell for the cost of them, if anyone interested. For the boat is a beauty either way!

We had built a 42′ Wharram, started a circumnavigation, crossed Pacific ocean over to Australia and then family ill and we came back to US. And then sold and financed and guy ran not paying, so that changed our budget to build the schooner.

We then shifted to redesigning a sailing scowl 38′-42′? Wanting Chinese junk sails. And now recently we’ve decided due to a scowl having some limitations crossing oceans, even though we were going to have a center board, we rethinking, as I just posted to you for a used boat, w/my thoughts of what I had designed w/the scowl, but would like more sea going. You must know how bad the sea can be w/your experiences? Even though we were not planning to do long passages again, it may happen, especially if we find a boat in another country? Due to my love of hardwood but can’t cut a hardwood tree. Especially if it was the African kwan deen wood!

I live now in a small `Buehler design sailboat, and I yet to talk to him about it. But never again would I live in a design that has compartments hard to maintain! But it is a very nice boat accept for that. I’ve tried to sell it but no go yet and we are thinking to give it to a wooden boat school, if we should find another we want.

There is still a chance we would build our next one, but as I asked for one already similar built, I too would retain the integrity of what I want taking ideas from the hull of a junk and others? This is what happens when we get to sensitive knowing what we want, then we have to work at it!

When we built the Wharram, we lucked out and found a 250 year old tree that had to be cut, and they cut it no knots, every board we needed all from that one tree, and I happened to find a good deal also and trucked it from WA to WI, where we built the boat. Then I lucked out again finding 2 semi drivers w/empty loads that gave us another deal hauling it to WA from WI.

Actually in the link below of our website I show a photo overlay of our Wharram in Solomon Islands, in our signature on each page, along w/another photo like a Chinese Junk, you may know of as well who did it, for I could not find an owner to ask permission to use it? As we named our project `i come to talk story from the Chief in Solomon Island, that would come visit us, and we would exchange ideas and he would paddle off to next island and share and then come back and we would do it over and over again!

So life is funny how we co_evolve, so good luck in your desires! And thanks again for such beautiful work from all!

kara

Good day Dan Ta Monster,

I am currently studying in the University of Hong Kong and engaging in a course project about the Eastern District in Hong Kong. I am planning to talk a bit about the shipyard in Shau Kei Wan, thus I am writing to seek permission for using the photos displayed in this blog. I am looking forward to your reply! Thank You!

Hi Athena,

Yes, you may use my photographs as long as you credit them to Billy Potts.

The old photographs of the older junks, however, are not mine and belong to Karsten Petersen Source: http://www.global-mariner.com. You will have to ask him separately for permission if you would like to use them.

I would be interested to read your study, if you are willing to share.

Billy

Great post!

I hope someone in hong Kong will be able to setup a race competition on tradition Chinese sailing boat and get company to sponsor in building new junk.

Round the island race! Like the cowes week on the isle of wight!

Living Art is the Junk Rig I so want to buy one to live aboard and sail the world in as the artist and musician I am! Where can I do so? Wonderful article thank u and if you’d consider a 54 year old apprentice for 2 years count me in ! X Mary Lale

Hello,

If anyone can share my comment w/Mr. Au Wei, I’d appreciate it. I tried to connect w/an email but no luck, but did find a tel of the Kwong Ming Shipyard. So may still call?

I would like to find a well built used sailboat like a sampan more so flatter than the shapes of the Traditional Chinese Junks w/raised stern, 38′-42′ by 12′ or so? Shallow 2-3′ flat deck/aft a cock pit to fish from, then 1 room cabin to live in, then flat deck for cargo or hold, then small cabin in bow. Chinese Junk Sails, kwun deen wood or like, for I can’t cut a hardwood tree down or even buy new?

So any leads to a good shape w/little or no repairs would be great!

We are a US nonprofit doing research yet to gain support, so low /no budget, until we gain support!

Thanks and w/this we intend to share humanity’s options to make peace/stop suffering thru doing local `plans, globally. C

Check out our site on Nabble; `i come to talk story

Peace, kara j lincoln